Health News

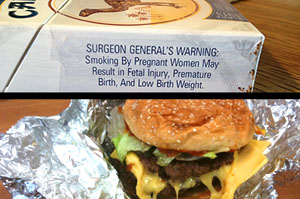

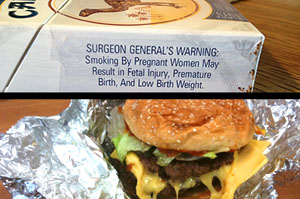

To make real headway in battling the obesity epidemic, lessons can be learned from the war on smoking ? though the two public-health issues have certain unique challenges. Judith Graham, reporting for Kaiser Health News in collaboration with USA Today, delves into the similarities and differences.

To make real headway in battling the obesity epidemic, lessons can be learned from the war on smoking ? though the two public-health issues have certain unique challenges. Judith Graham, reporting for Kaiser Health News in collaboration with USA Today, delves into the similarities and differences.

- Child Obesity Is A Complex Problem, Intimidating To Those Who Are Fighting It (last In A Series)

Dr. Christopher Bolling prepares to see a patient.By Tara Kaprowy Kentucky Health News Nearly every weekday, pediatrician Christopher Bolling starts his day by scooping up his lap top and stepping into one of his cheerfully-appointed exam rooms. After...

- Hbo's 'weight Of The Nation' Examines The Obesity Epidemic

A compelling four-part documentary delving into the obesity epidemic sweeping the country is being aired on HBO and can be watched free by clicking here. A reporter wanting to write a series of stories on the issue would find "weight of the Nation" a...

- Drug Abuse, Obesity Are Top Two Concerns For Children's Health, Poll Finds

Childhood obesity and drug abuse are the top two worries for children. Those were the results of a University of Michigan poll that asked people to rate 23 different health concerns for kids living in their communities. When it came to obesity and drug...

- Overweight People Tend To Cluster With Those Who Are Likewise

The adage "birds of a feather flock together" seems to apply when it comes to the obesity, with a study concluding that overweight people tend to befriend others who are overweight. Obesity also tends to run in families, with obese parents raising...

- Appalachian Health Summit To Be Held In Lexington Thursday

Focusing on obesity, a topic that affects most adult Kentuckians, the Appalachian Health Summit will be held Thursday in Lexington. The meeting is designed for clinicians and researchers, but will also be a place for journalists interested in the issue...

Health News

Lessons in battling obesity can be learned from the anti-tobacco movement, but there are big differences

Her piece deserves to be read in its entirety, which can be done by clicking here, but here's a summary of her analysis:

Children are central. The majority of people start using tobacco as teenagers, with one-third of kids who smoke daily set to die prematurely of tobacco-related illnesses. Likewise, overweight children are at a greater risk of a vast array of health problems, including diabetes, liver disease and obesity in adulthood.

Protecting children as at the heart of both the anti-tobacco and anti-obesity efforts. "First let's protect our children," said Dr. David Ludwig, a child-obesity expert at Harvard Medical School.

Changing social norms is the goal. While smoking in a hospital or airplane has become inconceivable, the same shift in social norms is required to fight childhood obesity. "Our (eating and physical activity) tastes, our preferences and our behaviors are learned and can be changed," said Dr. Jeffrey Koplan, former head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and vice president for global health at Emory University in Atlanta. It won't be easy, but at least "we're dealing with a population that would like to be thinner and that works in our favor."

We can't "just say no" to food. "Tobacco we can get rid of entirely," said Dr. David Katz, director of Yale University's Prevention Research Center. "But we have to eat to live and make terms with food as the enemy."

That makes fighting childhood obesity much more difficult, since the message can't be "stop, don't do this." It has to instead be "make good choices, set boundaries," which is more difficult to convey and adhere to, Graham reports.

Our biology works against us. "While smoking is highly addictive, the biological responses attached to eating food are even more deeply rooted in human evolution," Graham reports. Evolutionarily speaking, humans are "built" to eat food when it's available and "we're very good at storing calories and defending calories once we've got them," said Dr. Stephen Daniels, chair of the department of pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Shame and denial are greater among the obese. A person's self-image is tightly tied to his or her body weight in a way that isn't true of smoking. That can provide a compelling reason to stop over-eating, but people don't tend to think of themselves as obese. "Obesity is seen as a pejorative term that people don't connect with," said Dr. William Dietz, director of the division of nutrition, physical activity and obesity at the CDC. "They think, 'I'm just 30 or 40 pounds overweight, but I'm not obese.'"

There are more food products available. "Tobacco is a single substance," Graham reports. "By contrast, the food and beverage industry is enormous and makes a huge array of goods that extend into every home, restaurant, convenience store, and grocery store in America."

There is no second-hand smoke equivalent. "The notion that my behavior as a smoker can have an effect on you and can make you sick was critically important in accelerating people's intolerance of smoking and their willingness to see the government take action," said Michael Eriksen, director of the Institute of Public Health at Georgia State University. "Your being obese does not affect me in the same direct way."

The role of the food industry is less clear. While Big Tobacco was able to be demonized, "with obesity (as compared to tobacco) there's a much more nuanced relationship with industry," said Dr. James S. Marks, director of the health group at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

- Child Obesity Is A Complex Problem, Intimidating To Those Who Are Fighting It (last In A Series)

Dr. Christopher Bolling prepares to see a patient.By Tara Kaprowy Kentucky Health News Nearly every weekday, pediatrician Christopher Bolling starts his day by scooping up his lap top and stepping into one of his cheerfully-appointed exam rooms. After...

- Hbo's 'weight Of The Nation' Examines The Obesity Epidemic

A compelling four-part documentary delving into the obesity epidemic sweeping the country is being aired on HBO and can be watched free by clicking here. A reporter wanting to write a series of stories on the issue would find "weight of the Nation" a...

- Drug Abuse, Obesity Are Top Two Concerns For Children's Health, Poll Finds

Childhood obesity and drug abuse are the top two worries for children. Those were the results of a University of Michigan poll that asked people to rate 23 different health concerns for kids living in their communities. When it came to obesity and drug...

- Overweight People Tend To Cluster With Those Who Are Likewise

The adage "birds of a feather flock together" seems to apply when it comes to the obesity, with a study concluding that overweight people tend to befriend others who are overweight. Obesity also tends to run in families, with obese parents raising...

- Appalachian Health Summit To Be Held In Lexington Thursday

Focusing on obesity, a topic that affects most adult Kentuckians, the Appalachian Health Summit will be held Thursday in Lexington. The meeting is designed for clinicians and researchers, but will also be a place for journalists interested in the issue...